The last two years have seen a decline in hugging, a result of the social distancing that accompanied the two-years and running COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, removing the physical touch of a hug or other comforting gesture can negatively impact our health.

As we celebrate National Hugs Day on January 21, the simple gesture of compassion and celebration of a hug is actually a prescription for better brain health and caregiver wellness.

Hugging is an intimate gesture that brings two people together. The person receiving the hug gets a silent message from the hugger, “You matter to me, you are not alone, I’m here.” The emotional impact of this small act can make all the difference in the world to a family caregiver who is experiencing sadness, depression, fear and anxiety and often loneliness.

But scientists have established beyond the emotional uplift, there is a positive physical impact as well. When hugged, we receive a jolt of oxytocin – known as the “love or cuddle” hormone. This hormonal surge triggers endorphins that help us bond with the person we are hugging. There is a transfer of positive energy from one human to the other and we feel safer and supported.

Taking the science even further, receiving a hug can boost the immune system, calm our body and regulate blood pressure, reduce inflammation, improve restful sleep, bring balance back to our nervous system and make us more patient. In addition to the oxytocin hormone for a feeling of happiness and bonding, hugs also result in a dopamine release in our brains – the “feel good” and “reward system” hormone – which can relieve stress and tension as well as motiviate us and boost our self-esteem.

“We need 4 hugs a day for survival.

We need 8 hugs a day for maintenance.

We need 12 hugs a day for growth.”

Virginia Satir (1916-1988)

According to the Greater Good Science Center at the University of California at Berkeley:

“Touch is the first sense to start working in the womb (around 14 weeks). From the moment we’re born, the gentle caress of a mother has multiple health benefits, such as lowering heart rate and promoting the growth of brain cell connections.”

In research done in a NICU unit of a hospital, newborn babies were separated into two groups. The first group was cuddled and held in a warm snuggly embrace a few times a day. The other group was well-nourished and cared for but not held and hugged. After just a few weeks, researchers observed the first group thrived with higher weight gains, cooing noises and better sleep. The second group, which did not get their daily hugs, had lower weights, cried more often, were restless during sleep periods and appeared more agitated.1

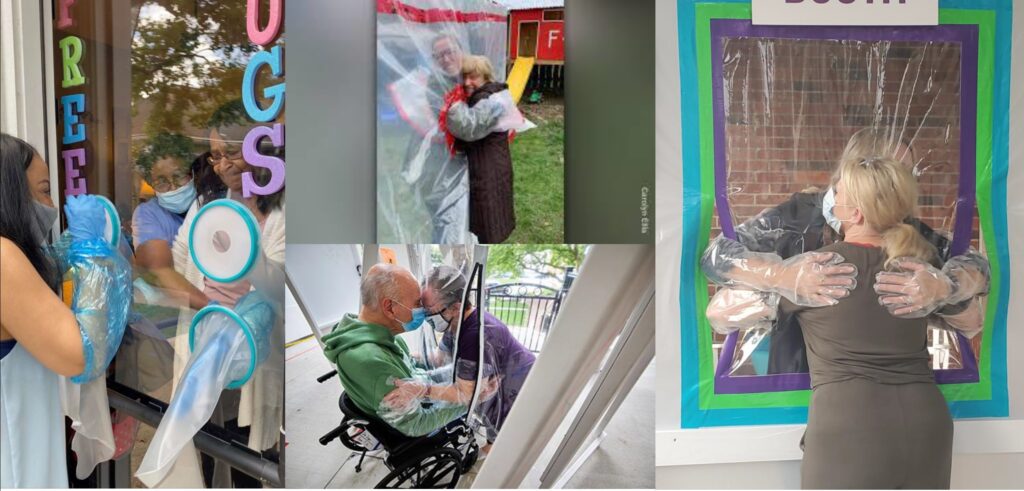

A similar study was conducted in nursing homes showing the therapeutic benefit not just for the senior residents but for the staff providing the hugs as well. In fact, during the height of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 when nursing homes, assisted living and other congregate living comminities shut down to outside visitors and physically isolated their residents, spontaneous “hugging booths” began appearing to provide virtual hugs between family members.2

Essentially, hugs are necessary for our survival. Without them, we are living a slow death. Psychologist and author Susan Pinker has written about the inability to have face-to-face contact has harmful effects on our health. . In her TED Talk, Pinker explained how social contacts create a vaccine not just for loneliness but as “a biological force field between disease and decline.”

Virginia Satir, a noted psychologist who specialized in family relationships and is referred to as the “mother of family therapy,” advisesd, “We need 4 hugs a day for survival. We need 8 hugs a day for maintenance. We need 12 hugs a day for growth.”

Hugs Protect Our Brains

The focus on brain health has taken on important significance in caregiver wellness. The increase of emotional health burdens among caregivers is alarming. Paul Zak, a neuroeconomist known as “Dr. Love” for his research into oxytocin and neuro response, prescribes eight hugs a day to receive the adequate amount of oxytocin and other hormonal release that provide a neuroprotective effect for brain health.

In addition to human to human contact, we can receive the same plethora of health benefits from hugging a dog or cat.3 It is one of the reasons why pet therapy is so powerful and impactful in our senior population and even helping to calm agitated or wandering dementia patients.

When I gave the keynote speech at the National Caregiver Expo in Jacksonville, Florida a couple of years ago, I spoke about the healing power of hugs. Spontaneously, the audience turned to each other and gave their fellow audience member a hug. Someone came up on stage to embrace me and I can’t explain the surge of positive emotion and feeling so good that I was there!

The best part of hugging is that it is a non-pharmacological, non-invasive, universal expression of love and care. And it’s the gift that gives back because we cannot hug someone without getting the same reaction we provide. Hugs are where both parties benefit in the emotional and physical healthy feelings.

How to Give a Good Hug

- Hug someone for at least 20 seconds – don’t be wimpy or weak about it – make it a good bear hug to show how much you care.

- Provide the “Heart to Heart Hug”: Raise your left arm up to wrap it over the upper right shoulder of your hugging partner, leaving your right arm low to wrap around his or her midsection just below his or her left arm.

- Include your pets in your daily prescription of 8 Hugs a Day – all hugs count!

- If you are not sure if someone is a hugger, a nice pat on the back or rub on the hand or arm will let you know if you should go for it. If not, the touch is still a nice gesture of support and not invading the recipient’s space.

References

1 Hilton, L. (2018). Hugging is healing for NICU babies. Contemporary Pediatrics, 35(5), 27-31.

2 Weisberg, J., & Haberman, M. R. (1989). A therapeutic hugging week in a geriatric facility. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 13(3-4), 181-186.

3 Petersson, M., Uvnäs-Moberg, K., Nilsson, A., Gustafson, L. L., Hydbring-Sandberg, E., & Handlin, L. (2017). Oxytocin and Cortisol Levels in Dog Owners and Their Dogs Are Associated with Behavioral Patterns: An Exploratory Study. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 1796. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01796

©2022 Sherri Snelling

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks